The South Korean beauty industry is onto a good thing with the oil extracted from the nut of the tamanu tree. Tamanu oil not only moisturizes dry skin, as widely advertised, but it also restores burned and degraded land, revives local farming economies, and could even save lives.

The tamanu nut tree is known by a variety of names, many given to it by the many generations of people who have lived with them across tropical Africa, to South and Southeast Asia and beyond to Oceania.

Scientists and researchers call the tree calophyllum inophyllum, while groups of Indonesians indigenous to the Kalimantan provinces of Borneo know it as bentanur and others on Java as nyamplung.

Alexandrian laurel, kamani, bitaog, pannay and sweet-scented calophylum are only some of the names people use for tamanu in the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Melanesia, Sri Lanka and Timor Leste.

Most fittingly perhaps, considering the way tamanu is gaining global attention, some Polynesians reportedly call it the “beauty leaf”. Why they might is no mystery. Many generations of Polynesians – and many others all the way westwards to Africa – have been using the oil of the tamanu nut as a skin moisturizer and a healing balm. The oil also serves as a traditional hair tonic and for treating acne, dark spots, athlete’s foot and sunburn.

These apparent properties of tamanu nut oil did not long escape the notice of the beauty industry in South Korea and elsewhere – even before they got the attention of the medical world. Several South Korean skincare brands, such as Sidmool and Tosowoong, prominently feature their common key ingredient of tamanu oil.

The oil is widely advertised, with ready acceptance by numerous buyers, to be capable of reducing wrinkles, dark spots and hyperpigmentation, among others. Industry marketing claims that since the oil is rich with vitamin E, anti-inflammatories, antioxidants and fatty acids, it not only moisturizes dry skin, but actually heals it.

A beauty blogger, who publishes as Kane Turtle on the Korean Beauty page of the Amino app, investigated the considerable anecdotal evidence supporting the effectiveness of tamanu oil products by trying them out on herself.

She wrote in 2019 that while not everything worked as advertised, she did see some improvements.

“I…started using it as a spot treatment and saw significantly more results. A lot of my dark spots have been fading while my hyperpigmentation still needs some work.”

More methodical research had already been carried out several years earlier. A group of 11 scientists, including Teddy Léguillier and Marylin Lecsö-Bornet, experimented on five samples of tamanu oil collected from Indonesia, Tahiti, Fiji and New Caledonia to discover whether there was merit to the many medicinal claims made by its traditional users.

The paper they published in 2015 in the PLoS One science journal said the researchers had set out to discover if the oil truly had cytotoxic, wound healing, and antibacterial properties.

They found several things:

First, depending on the oil’s origins, it was safe at concentrations of between 2.7 and 11.2 per cent for the kind of cell that makes up 90 per cent of the outer layer of skin;

Second, cells incubated in the oil enjoy a 1.3 to 2.1 increase in their “healing factor”, as compared to cells that had minimal exposure;

Third, the oil is effective against conditions like acne because it inhibits the growth of one kind of bacteria (Gram+) and encourages the body’s defensive response against another (Gram-).

“Using cell and bacteria cultures, we confirmed the pharmacological effects of CIO [calophyllum inophyllum oil] as wound healing and antimicrobial agent,” the research paper concludes. “For the first time, this study provides support for traditional uses.

Traditionally in at least one place – the Philippine island of Luzon – the oil has also been used in lamps. Today it is a prime candidate for producing bioethanol and biodiesel in industrial quantities.

In Indonesia, also, traditional oils with a nyamplung oil content of more than 50 per cent have been produced with production reaching about 1 million bottles per month.

The Indonesian Ministry of Forestry and Environment’s Research and Development Agency (FORDA) and CIFOR researchers have determined that one hectare can produce 10 tons of fruit instead of crude oil.

That oil, once processed into some kind of biofuel, is reported to produce low amounts of harmful emissions.

However, despite encouraging signs, tamanu oil has still not proven itself to be a commercially viable alternative source of bioenergy. If it does fulfill its promise, tamanu oil could help the Indonesian government meet its still-distant goal of 20 to 30 per cent biodiesel and bioethanol in the national energy mix by 2025.

Two other traditional uses of the tamanu tree are more small-scale: The wood is highly valued as timber, especially as material for building boats, and the flowers are a favorite of bees.

The honey they produce is popular and lucrative. Farmers who maintain tamanu plantations near Wonogiri on Java in Indonesia report that their income from the nut oil was lower than expected, but selling honey was highly profitable.

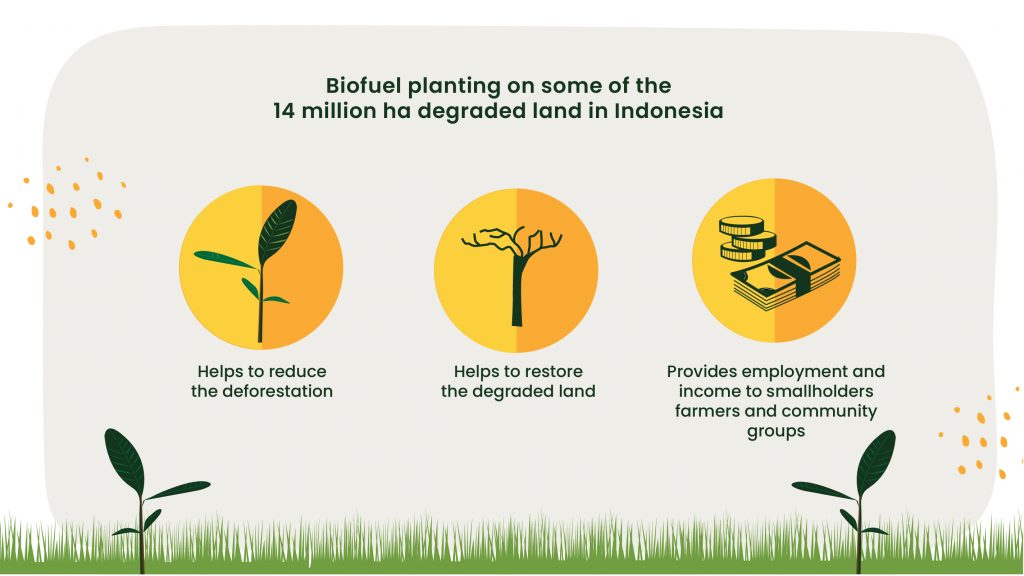

FORDA and CIFOR researchers and others are exploring another benefit that shows early potential: tamanu’s ability to restore and improve former forest and peatland either burned over or degraded by industry, overuse, or deforestation.

A degraded site in the Bukit Soeharto Research and Education Forest of Mulawarman University has been restored as an energy forest in three years, according to Dr. Sukartiningsih, the head of the Center for Reforestation Studies in the Tropical Rain Forest at Mulawarman University.

“The burned area was covered with bamboo shrubs,” she said. “Tree survival rate is more than 95 per cent and the growth is very fast, although it has to compete with the speed of the closing-in bamboo bush. [We are] very optimistic that establishing bioenergy forests with nyamplung would accelerate the rehabilitation program in a burned site, and even in an ex-coal mining site.”

Indonesian researchers estimate 3.5 million hectares of degraded or burned land across the country would be suitable for planting tamanu trees, since they improve soil function and promote local biodiversity. Farmers who are already cultivating tamanu on formerly degraded land usually intercrop it with maize, rice, cassava, soybeans and peanuts. The latter they keep to feed their families; the oil and honey they sell for cash.

Experimental plantations on degraded land in Indonesia’s Wonogiri, East Kalimantan and Central Kalimantan from 2017 to 2020 are spurring optimism.

“Nyamplung has been proven to be able to grow and well adapt in burnt areas with fertilizer treatment,” according to Dr. Budi Leksono of the Environment and Forestry Ministry, as quoted in a report published in June 2020. “Even more, the exciting finding shows that the tree has begun to flower and bear fruit after two year planting and it brings in several species of birds and insects…which indicate an increase in biodiversity in the ecosystem.”

Dr. Himlal Baral, a CIFOR senior scientist in the Climate Change Energy and Low Carbon Development Team, stressed in a direct communication that the trial plantations are still at an early stage. No nuts, he said, had yet been harvested, so the annual yield of oil is still unknown. However, he added that the trees show “promising” survival and growth, even those planted on a variety of degraded lands, including peat swamps.

“Growing tamanu trees under climate smart agroforestry system can support climate goals while supporting livelihoods for rural farmers,” Baral added.

“The market for nyamplung oil is not really developed yet,” said Budi Leksono, “but we’re anticipating an energy crisis and we are preparing for the plantations of the future.”

Dr. Sukartiningsih, who said the species even helped rehabilitate former mining sites, added that if enough nyamplung trees were cultivated, Indonesia could quickly become a net exporter of the valuable oil.

“Why not? This plant has every prospect of being developed in Indonesia. The growth is fast…before two years they start to flower and bear fruit. With good management they will produce a lot of fruit and produce the expected oil and other products.”