Indonesia has implemented a strategic approach to managing its extensive peatland ecosystems found across the archipelago, which will allow the country to meet goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 29 percent.

The strategy was unveiled at COP 25 climate talks in Madrid by Ruandha Agung Sugardiman, the country’s Director General for Climate Change, Ministry of Environment and Forestry.

The country – which has a significant presence in a dedicated pavilion featuring an eclectic array of international speakers, national cuisine and arts and crafts – is preparing its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to enable a more effective approach to achieving ambitious goals, Sugardiman said.

NDCs are a key part of the U.N. Paris Agreement strategy to prevent post-industrial average temperatures from rising to 1.5 degrees Celsius or higher. Each country is required to provide data on greenhouse gas emissions and reductions targets it aims to meet post-2020.

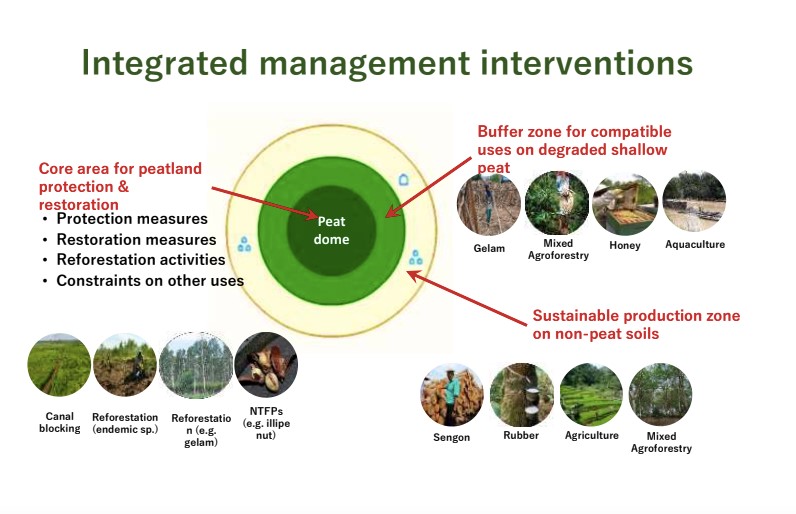

By categorizing the peatland areas through integrated management interventions, we can better conserve them, Sugardiman said, explaining how the approach involves dividing the carbon-rich ecosystems into concentric rings around a “peatland dome.”

The dome is a core area for conservation and restoration, the ring around the dome is a buffer zone for compatible uses on degraded shallow peat and the outer ring provides space for sustainable production on non-peat soils.

“We can conserve the peatlands much more safely,” Sugardiman said. “The activities will be protection measures, restoration measures, reforestation activities and concentration on other uses.”

PEATLAND SCOPE

Fewer than a dozen countries have so far included peatlands in their Nationally Determined Contributions, although the carbon-rich ecosystems exist in 180 countries, according to an international expert speaking on the sidelines of the U.N. climate talks in Madrid.

Peatland mapping and monitoring can help overcome barriers to climate action.

“Seven out of 197 parties have mentioned peatlands as a strategy – 3 percent,” said Martial Bernoux, a natural resources officer with the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), at an event hosted jointly with the Indonesian government.

“We have many more than 3 percent with peatlands; we have peatlands everywhere,” he said.

Indonesia has made a strong commitment to restore 2.4 million hectares of drained peatlands. The country, considered a leader in peatlands research, is part of the Global Peatlands Initiative and is the founding country of the International Tropical Peatlands Center (ITPC).

“This is really an example for the world,” said Bernoux, who was detailing a systematic approach through which countries could gather their peatland data for inclusion in NDCs.

The other countries include Afghanistan, Belarus, Brunei, Burundi, Rwanda and Uruguay.

NDC progress and climate pledges are monitored under the Talanoa Dialogue. NDCs are under close scrutiny because under current pledges the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports with high confidence that global warming is expected to surpass 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, even if they are supplemented with substantial increases in the scale and ambition of mitigation after 2030, according to the 2018 IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C.

Improving the capacity for countries in the Global South is central to establishing a successful collaboration for a country-driven agenda for peatland action, Bernoux said, explaining that barriers to sustainable peatland management include economic, institutional, technological and legal factors.

Known as bogs, mires, moors and muskegs, peatlands are vital carbon sinks. They make up more than half of all wetlands worldwide and they are equivalent to 3 percent of total land and freshwater surfaces.

Built up over thousands of years from decayed, waterlogged vegetation debris, Wetlands International reports that 15 percent of peatlands have been drained for agriculture, commercial forestry and to extract fuel.

When they are drained, they oxidize and carbon is released into the atmosphere, causing global warming.

A third of the world’s soil carbon and 10 percent of global freshwater resources worldwide are stored in peatlands, according to the International Mire Conservation Group and the International Peat Society.

The Global Peatland Hotspots Map published in 2015 by the Conventions on Biological Diversity, Wetlands (Ramsar), and Desertification (UNCCD) shows that 25 countries are responsible for 95 percent of global emissions from peatland drainage, excluding fires.

New guidelines from the IPCC have separated peatland and mangrove ecosystems. These wetlands ecosystems were formerly lumped together with the AFOLU (Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use) Guidelines, said Daniel Murdiyarso, a principal scientist with the Center for International Forestry Research, who moderated the event, which was titled “Gearing towards NDC ambitions with C-rich peatlands in the agenda.”

“The ‘2013 Supplement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Wetlands‘ should be used in the next round of NDCs submissions,” said Murdiyarso, an expert in peatland and blue carbon ecosystems, who has been a Convening Lead Author on the IPCC Guidelines, Special Reports and Assessment Reports.

Ecosystem restoration and protection are considered contributors to a Nature-Based Solution (NBS) to the climate crisis. Research suggests that NBS could provide around 30 percent of mitigation that is needed by 2030 to curb global warming, according a report by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and the University of Oxford.