A new cost-effective, community-based monitoring system is giving land management strategies a boost in Riau province as the Indonesian government rolls out techniques that empower local communities to reduce fire susceptibility in peatland areas.

Through the Community-based Peatland Restoration Monitoring System (CO-PROMISE) led by scientists with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Riau University and the local government, local residents are using the 3R restoration technique: re-wet; re-vegetate and re-vitalize livelihoods.

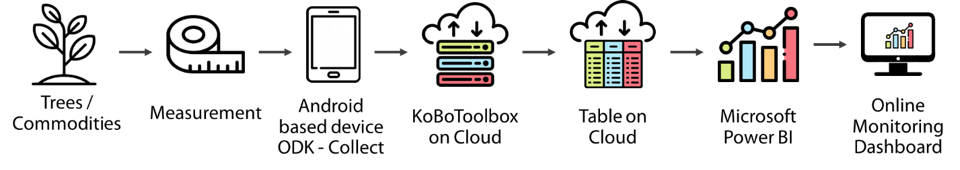

The process involves measuring groundwater and moisture levels in peatlands. It also involves recording tree re-vegetation and livelihood revitalization efforts by tracking and sharing data on pineapple and coconut harvests.

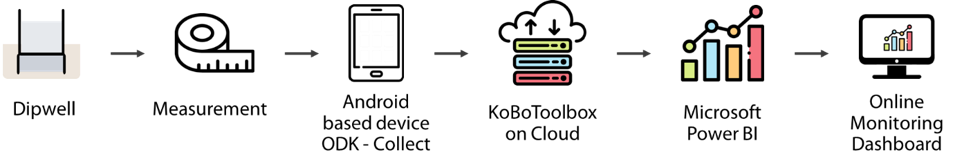

Under the initiative, farmers learn how to store data in Android-compatible free, open source software hosted by Open Data Kit. They can enter the data onsite while they are at work in their fields and upload their findings later when their mobile devices are connected to the Internet.

“We hope the project gradually influences and changes the behavior of local communities – and beyond – in terms of practicing land clearing without using fire, participating in peatland restoration, and that it improves their livelihoods through sustainable business models,” said CIFOR senior research officer Beni Okarda who collaborated with CIFOR wetland ecologist Imam Basuki to develop the application.

The project, helmed by CIFOR scientist and systems modelling expert Herry Purnomo, uses an approach known as Participatory Action Research (PAR) to implement and foster effective Community-Based Fire Prevention and Peatland Restoration (CBFPR).

The work involves reviewing best practices related to CBFPR, including developing and testing peatland restoration practices and land clearing without using fire, and sharing lessons learned, and successful outcomes.

“Ultimately, we expect to produce reports, guidelines, and an action area showcasing the PAR-CBFPR process for scaling-up at the national level and beyond,” Basuki said. “This system, which is based on open source and free software, can be widely implemented for those who are working on monitoring the water table and soil subsidence in peatlands, as well as monitoring tree growth as part of peatland restoration program.”

System workflow

In CO-PROMISE we are using android based ODK-Collect that can be operated offline to input measurements results. Trained community members are voluntarily doing the measurement in monitoring dipwell, input data measurements, and submit it to the database once it connected to the internet. To minimize human error in data input, we are setting the input value in a reasonable range and keep manual documentation using a logbook for further cross-check if needed.

TRANSFORMING TECHNIQUES

Until recent times, farmers used swidden techniques, also known as shifting cultivation or, formerly, “slash and burn” to prepare the land for planting. Under this system, natural vegetation is cut down and burned. Over time, as land becomes infertile, farmers move to new areas and repeat the process, which results in degraded scrubland areas.

The technique dries out peatlands, which are carbon sinks comprised of layers of decomposed organic material built up over thousands of years. Worldwide, they store a third of the world’s soil carbon, according to the International Mire Conservation Group and the International Peat Society.

When they burn, peatlands, which are found in 180 countries, release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which cause global warming.

In some years, fires can burn out of control in arid, hot conditions exacerbated by El Nino or positive Indian Ocean Dipole weather systems.

Environmental and health concerns led the Indonesian government to place a moratorium on land clearing almost 10 years ago, and CIFOR has been working with Indonesia’s Peatland Restoration Agency to aid in developing land management and restoration activities.

LOCAL LESSONS

For CO-PROMISE, the area of focus has been in Dompas Village of Bengkalis Regency and five satellite villages northeast of the provincial capital Pekanbaru. The local landscape features primary and secondary forest, privately-owned mixed cultivation gardens, monoculture rubber plantations, oil palm plantations and shrub or abandoned, degraded land.

The area was selected because it has a substantial post-fire area, and demonstrates the need for intensive fire prevention and peatland restoration. The area is also scarred with canals used in palm oil production, characterized by water channels constructed in forests that cause peat to dry out.

“All stakeholders involved in this project can easily monitor the progress and impact from this project through monitoring dashboard,” Okarda said. “For example, we can clearly see that the canal blocking makes the water level 16 cm higher than areas that don’t have canal blocking. This condition makes area with canal blocking are less prone to fire, than those without.”

Peatlands are known for their biodiversity, and Dompas is no exception. There are many valuable species native to the peatland ecosystem, for example meranti (Shorea spp.), often used for timber, and ramin (Gonystylus spp.), used for furniture making.

Various animals, such as owa-ungko (Hylobates agilis), siamang (Symphalangus syndactylus), lutung (Trachypithecus cristatus), long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis) and beruk (Macaca nemestrina) are frequently found in local forests and plantations. A number of protected species, including the Sumateran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) and honey bear (Helarctos malayanus) have been sighted in forests.

Indonesia has the third largest peatland area in the world, after Russia and Canada.

Worldwide, peatlands make up more than half of all wetlands. They are equivalent to 3 percent of total land and freshwater surfaces.

Overall, Indonesia has committed to restore 2.4 million hectares of drained peatlands.